Neutrinos are very small, very light elementary particles which are able to travel through most matter with ease. They are among the most abundant particles in the universe, but they're often called 'ghost particles' because of how little they interact with matter!

Unlike electrons or quarks, neutrinos are electrically neutral. They can also change 'flavors' - evidence that they have mass, which the original Standard Model didn't predict. This mass is much smaller than any other particle mass in the Standard Model and at least a thousand times smaller than the electron.

Neutrinos can travel across our universe. They can give us unique information about the Earth, Sun and supernovae. Their ability to undergo flavor oscillations can also be used to directly test the Standard Model of particle physics.

Neutrinos exist in three flavors: electron (e), muon (μ), and tau (τ). When travelling, neutrinos 'oscillate' (or change) between these flavours.

We know neutrinos have mass since we have observed them oscillate from one flavour to another. In 2015, physicists Takaaki Kajita and Arthur B. McDonald received a Nobel prize for proving the existence of neutrino oscillations via experimentation, directly implying that neutrinos have a non-zero mass.

The discovery of neutrino mass has become one of the main motivations for physicists to look beyond the Standard Model. Measuring the absolute neutrino mass may also help us understand more about how particles gain mass.

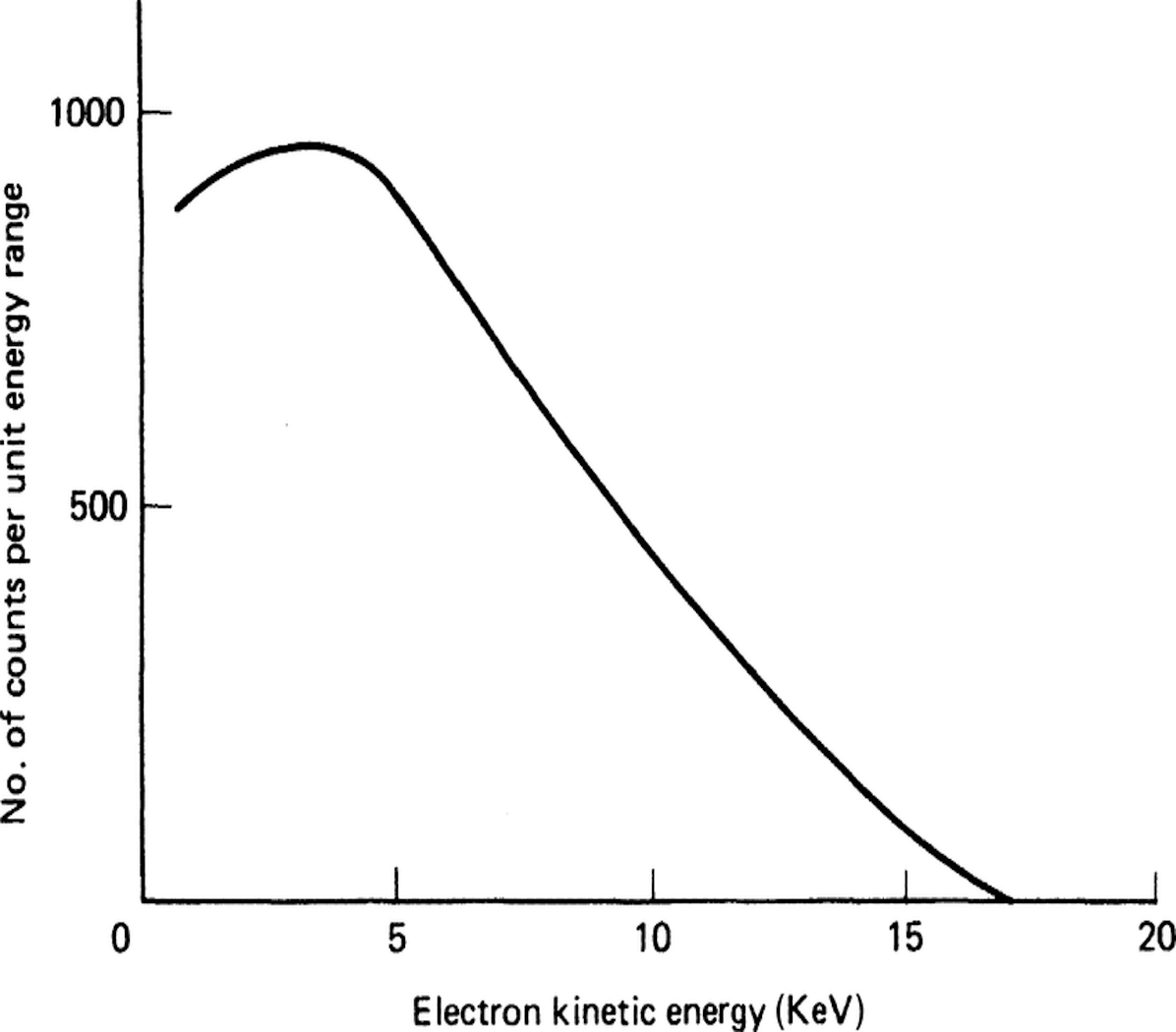

There are three primary techniques for measuring neutrino mass, which have been developed and refined over different time periods. These methods include cosmological measurements and data, which have become more precise in recent decades; neutrinoless double beta decay, a process still under investigation; and direct measurements from the endpoint of the beta decay spectrum.

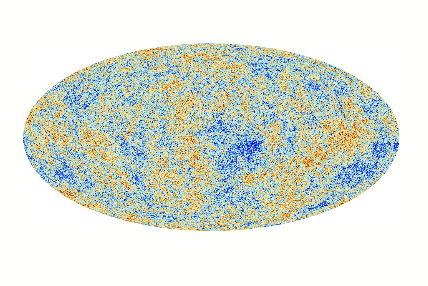

This approach is based on the cosmological effect of the relic neutrino background on the cosmic microwave background (CMB) and the structure of the universe. The current limit is \(\sum{m_{\nu}}\ {<}0.115eV/{c}^2\) measured to 90% accuracy (where \(\sum{m_{\nu}}=\) the sum of the neutrino masses \(= m_1+m_2+m_3\)).

However this method of measurement is model dependent, and so is weakened if a specific cosmological model is not used.

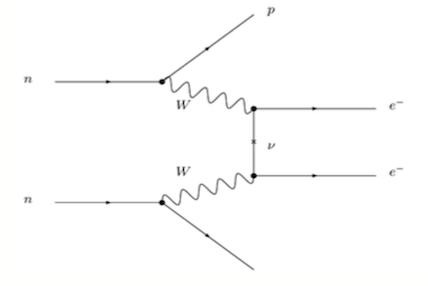

Neutrinoless double beta decay involves the transformation of two neutrons into two protons and two electrons, without the two antineutrinos observed during "two neutrino" double beta decay. The two electrons emitted share the full available decay energy.

However this type of double beta decay has not yet been observed. Also, like the cosmological method, this approach is model dependent, assuming that neutrinos are Majorana particles (i.e. their own antiparticle).

Using only energy conservation calculations, this method uses the information we know from beta decay (the energy required to form an electron Ee, the kinetic energy of the electron Ekine and the kinetic energy of the neutrino Ekin\(\nu\), which is zero at the maximum electron kinetic energy) to find the energy required to form a neutrino. From this energy value, the neutrino beta decay mass mβ can be calculated.

This process is model independent, only relying on the most basic laws of nature! We'll use this for QTNM while measuring the beta decay of tritium (click here to find out how).

\[Q_\beta = \color{royalblue} {\underbrace{{e_{mass} + e_{energy}}}_{\text{electron mass and energy}}} + \color{tomato} {\underbrace{{\nu_{energy} + \nu_{mass}}}_{\text{neutrino mass and energy}}}\]

The limits on the neutrino mass are given by \( m_{\beta} = \sqrt{ \sum_{i} \left| U_{ei} \right|^{2} m_{i}^{2} } \), where \( m_i \) are the neutrino mass eigenstates. Mass splittings obtained from neutrino oscillation experiments provide a lower limit on \( m_{\beta} \). For normal ordering, we expect \( m_{\beta} \geq 9 \) meV, and for inverted ordering, \( m_{\beta} \geq 50 \) meV. An experiment with sensitivity below \( m_{\beta} = 50 \) meV can determine the mass ordering, while a sensitivity of 9 meV guarantees a discovery of the neutrino mass.

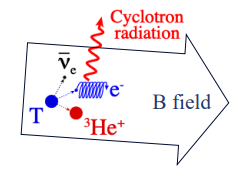

Cyclotron Radiation Emission Spectroscopy (CRES) is a key technique employed in our project, with the concept originally pioneered by the Project 8 collaboration led by Monreal and Formaggio. In this process, electrons emitted from beta decay are immersed in a magnetic field, leading to the emission of cyclotron radiation as they undergo cyclotron motion (i.e. as they spiral). The frequency of this radiation is solely dependent on the kinetic energy of the electron and the strength of the magnetic field: \[f = \frac{1}{2\pi}\frac{eB}{m_e+{E_{\text{kin}}}/c^{2}}\] For our specific setup, the kinetic energy Ekin (or Qβ) is 18.6 keV, and the magnetic field strength B ~ 1 Tesla. This results in radiation with a frequency f of 18GHz and a wavelength λ ~ 1cm, falling within the microwave radiation spectrum. The emitted radiation is collected using specialized detection systems such as an antenna waveguide or a resonant cavity. These features make CRES an invaluable tool for high-precision measurements, allowing us to probe the properties of neutrinos with unprecedented accuracy.

Small Radiated Powers:

One of the significant challenges in CRES is the extremely low levels of radiated power, which requires extremely sensitive instrumentation to capture and analyze the emitted radiation effectively. For a magnetic field of B ~ 1 , Tesla and an angle θ = \(\frac{\pi}{2}\), the radiated power is extremely low, ~1 femtowatt.To mitigate this, QTNM aims to use quantum amplifiers to amplify the signal.

Additionally, maintaining the atomic state of tritium over extended periods is technically demanding and poses a key challenge for any future experiment employing CRES

The goal of our experiment is to determine the absolute neutrino mass with an ultimate sensitivity that could allow access to values approaching the lower bound of ~10 meV/c2. This will be done by measuring the energy of electrons emitted in β-decay of atomic tritium using CRES.

Due to the non-zero mass of the neutrino, the energy spectrum of the electron is altered, thereby generating a specific cyclotron frequency.

From this frequency value, we are able to calculate the radiation energy, which in turn will provide us with the absolute mass of the neutrino.

Using this model-independent approach, this project opens opportunities for model-independent kinematic searches for sterile neutrinos.