Molecular tritium introduces additional rotational and vibrational energy states, which act as a

background in the energy spectrum. This background can distort the endpoint measurement,

hence affecting the precision with which the neutrino mass is determined.

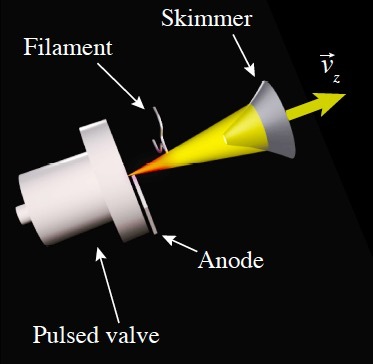

To create a simpler system for our precision measurement, we need to break down

molecular tritium \(T_2\) into atomic tritium \(Tr\). This is done through a process

called molecular dissociation.

Click here for more info about CRES

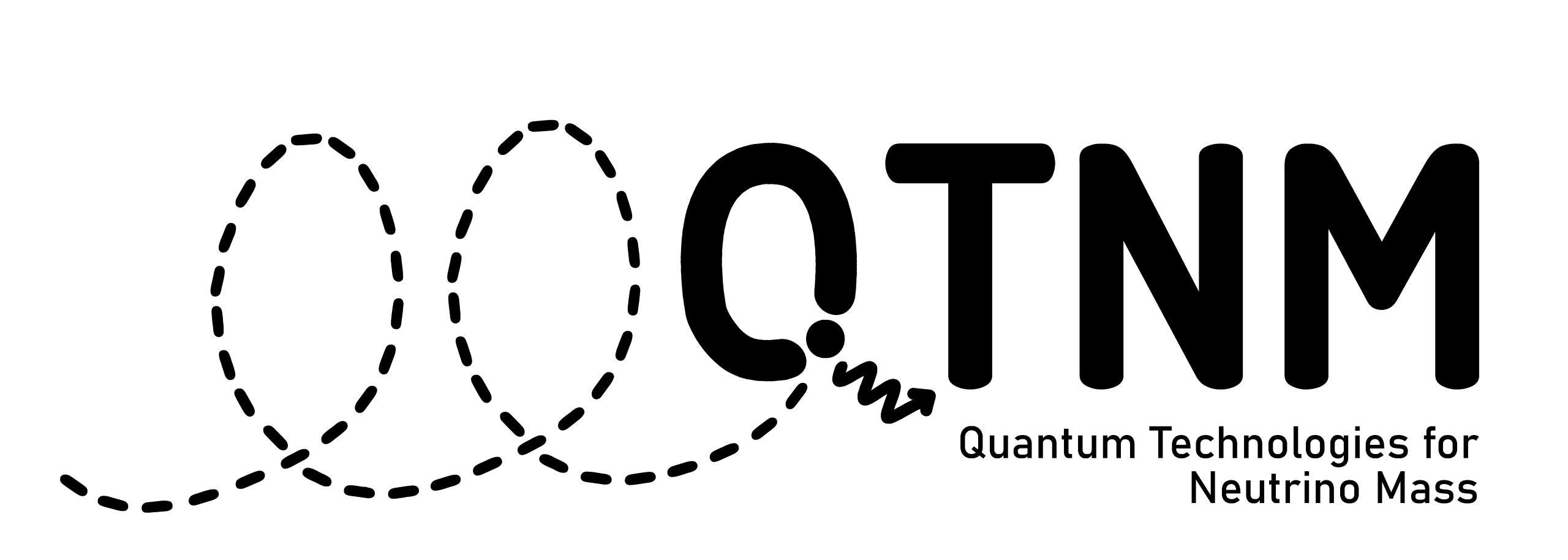

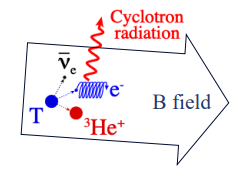

When a decay takes place, an electron is emitted into a uniform magnetic field (or B field),

which is produced by a large magnet. The electron moves in a helical path within the magnetic field,

emitting cyclotron radiation as it spirals.

The CRES region is where we collect this radiation.

However this comes with a challenge. The emitted electrons are incredibly fast – near-relativistic

in speed – and need to be measured for >20µs in order to collect enough power to determine the

kinetic energy of these electrons.

We also expect an extremely tiny signal on the order of femtowatts, with minimal thermal noise, especially since

the CRES region is maintained at 4 Kelvin (almost -270°C!).

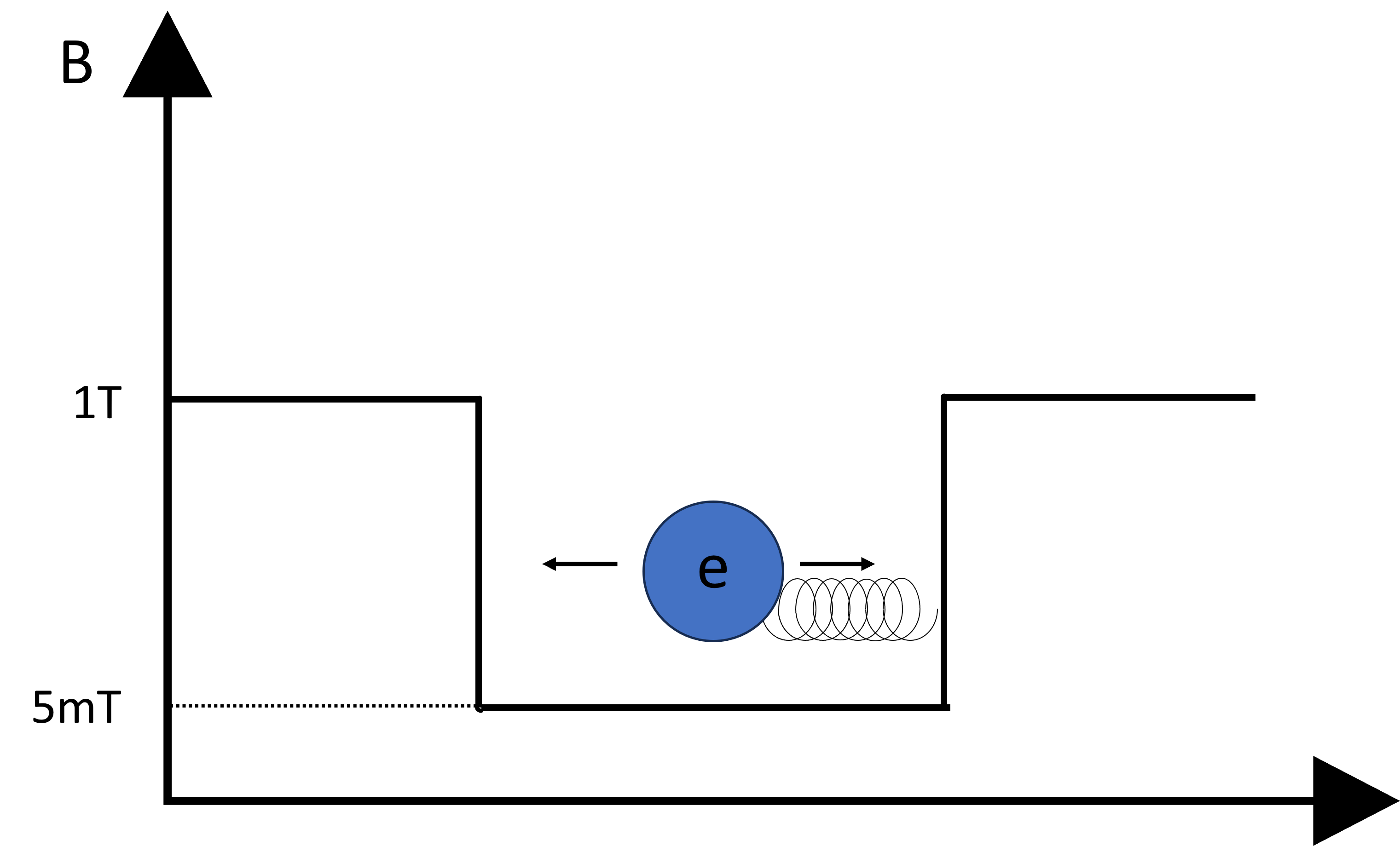

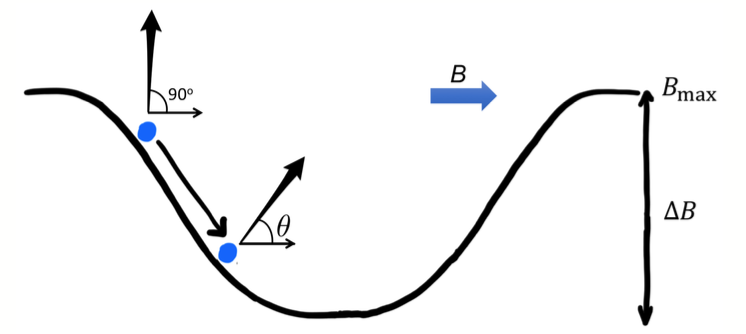

To resolve this, a 'no work' magnetic trap is placed within the uniform B field. The emitted electron bounces

back and forth within this trap as it spirals, allowing us to observe it for a longer period of time.

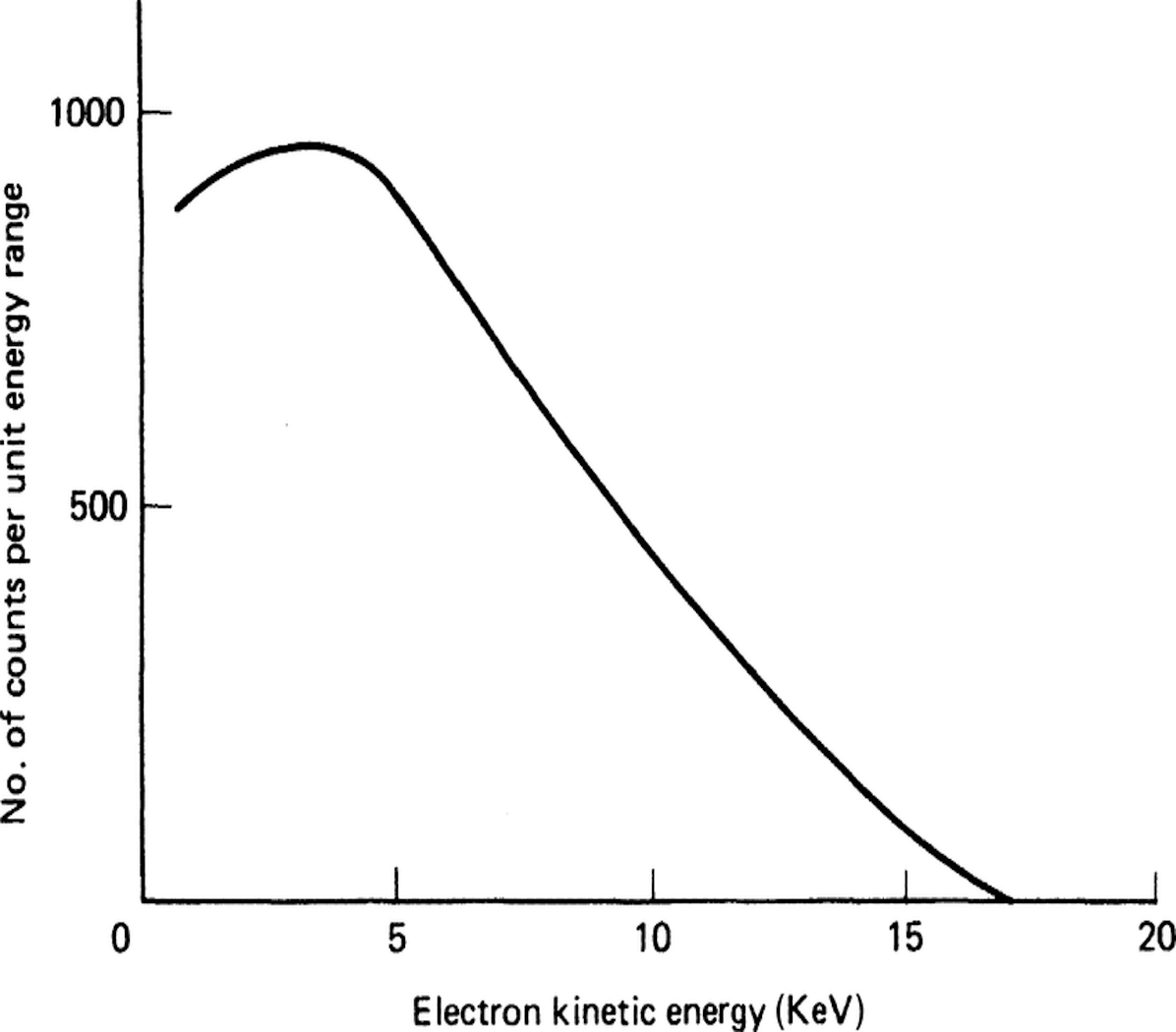

Our aim is to observe signals towards the endpoint of the spectrum - in other words, we want to make the detector

'blind' to background.

As we move towards lower energy levels, the frequency increases, meaning the chosen bandwidth

(i.e. the window of frequencies observed) will affect if the signal is observed.

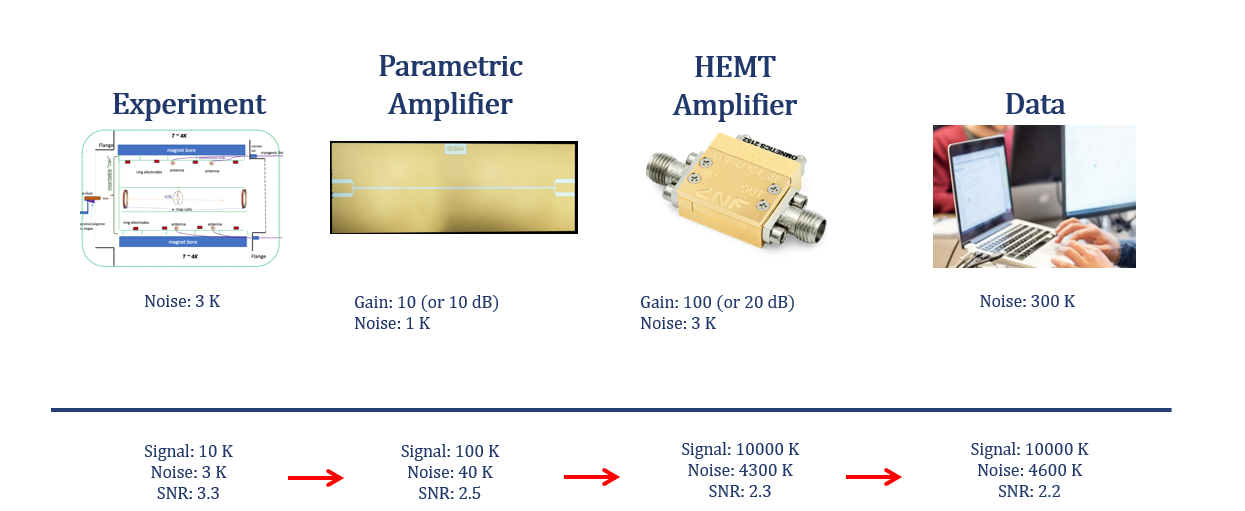

The signal is so small that thermal noise is background - we want to reduce this noise (and hence increase the

signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)) as much as possible.

The small collected signal is amplified using a quantum amplifier, which boosts the signal

power to a level where thermal noise is no longer a concern. These are also

designed to operate at the fundamental noise limit, offering the potential for significant

improvements in signal detection.

Quantum Limited Microwave Amplifiers

The CRES signal in the experiment is notably weak, with an approximate power of 1 femtowatt.

While state-of-the-art High Electron Mobility Transistor (HEMT) amplifiers offer noise

temperatures around 7K, QTNM's requirements call for the use of

quantum-limited amplifiers for enhanced sensitivity. Two types of quantum-limited amplifiers are under consideration:

these amplifiers operate at the quantum limit of noise performance, making it possible to

detect extremely weak signals with high accuracy.

QTNM will use a range of techniques from different disciplinaries disciplines, such as atomic physics,

experimental physics, and quantum technology to achieve our long-term goal of determining

mβ.

More information about our experiment can be found in

the QTNM white paper.